Diseases

| |

Mosquito Borne Diseases

Mosquito borne diseases and other vector borne diseases have long plagued humanity. Unfortunately, modern times are no different. Globally vector borne diseases infect 96 million people and kill 700,000 people annually. Most of these deaths are from malaria.

The disease landscape is continually changing. Human impacts such as climate change, travel and commerce have allowed both mosquitoes and diseases to expand their ranges. In 1999 West Nile Virus was introduced into New York City. It quickly spread throughout the United States including Massachusetts. Recently, the disease landscape changed again when Zika and Chikungunya were imported into the Americas. Neither of these diseases are currently in Massachusetts.

Massachusetts' main mosquito borne diseases are Eastern Equine Encephalitis and West Nile. The Department of Public Health is the lead state agency for disease surveillance and control. Mosquito control agencies work closely with DPH and participate in the surveillance program and in the control of disease outbreaks.

| |

Introduction

Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) is a rare form of viral encephalitis that is transmitted by mosquitoes. (The word encephalitis is a medical term for swelling of the brain). Massachusetts is one of the most active areas in the country for Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus. The first evidence of EEE virus was recorded in Massachusetts in 1831 when 75 horses were infected. The first human infections were recognized in 1938 during an outbreak in Massachusetts in which 38 people contracted EEE.

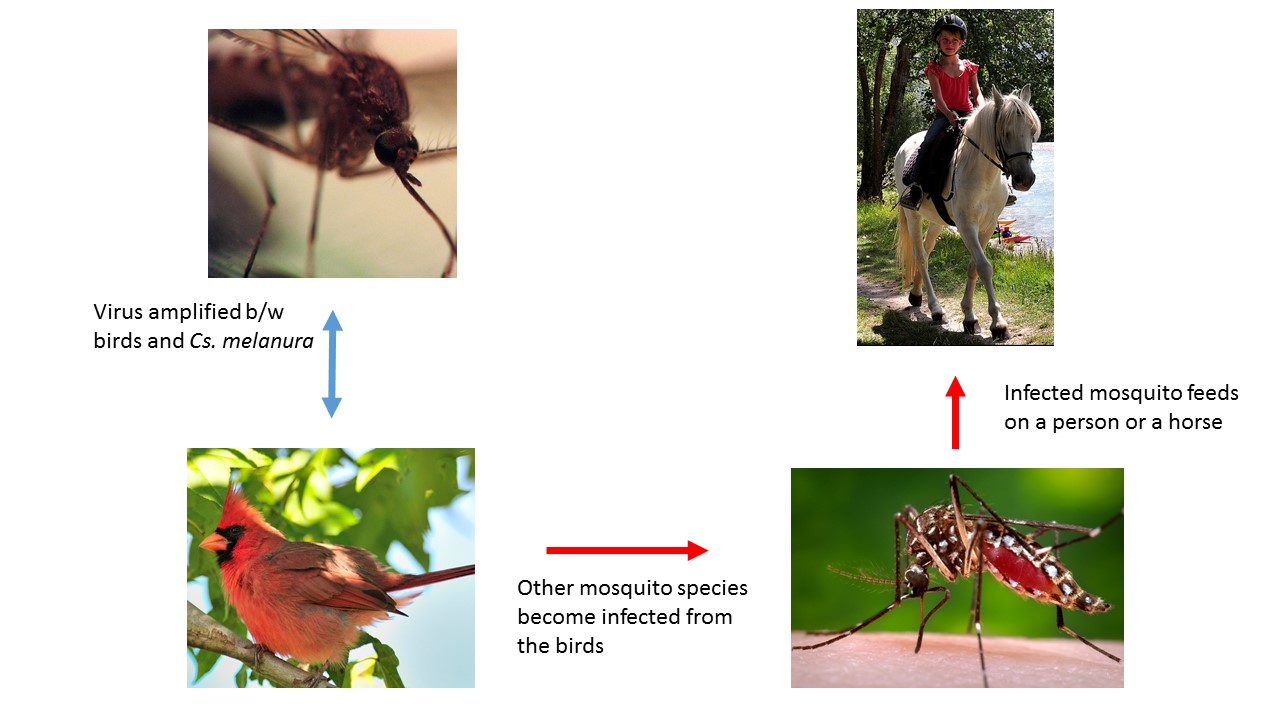

Transmission Cycle

How serious is EEE and who is at greatest risk?

- People at greatest risk for developing EEE are under the age of 15 or over 50.

- The CDC reports that about 35% of the people who contract EEE will die.

- 35% of survivors will have long term neurological deficits.

Prevention

- Use EPA registered insect repellents.

- When possible wear long sleeve shirts and pants.

- Avoid being outside at dusk and dawn or when mosquitoes are active.

- Remove containers and other sources of standing water on your property.

PCMCP's Actions

- Public education

- Submits mosquitoes to Massachusetts Dept. of Public Health for disease testing.

- Restores water flow to ditches to deuce mosquito habitat.

- Treats standing water when mosquitoes are present.

- Increases adult mosquito control in areas with virus activity.

Other State Government Actions

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MA DPH) manages a statewide network of mosquitoes traps.

- MA DPH tests mosquitoes for EEE virus.

- Public outreach and notifications.

- Arbovirus Surveillance and Response Plan is updated annually.

- Manages large scale aerial aduliticiding in accordance with the Arbovirus Surveillance and Response Plan.

Photo credits:

Mosquito by Cristiano Medeltro Dalbem, Creative Commons License

Cardinal by Bill Chitty (photo cropped) www.flickr.com/photos/41133154@N05/16196358520, Creative Commons License

Horse and rider by Stefan Schmitz (photo cropped), www.flickr.com/photos/stefanschmitz/6017526843/in/album-72157623946762843/, Creative Commons License,

Introduction

West Nile Virus was first identified in the West Nile district of Uganda in 1937. In 1999 the virus was introduced into New York City, from there it spread quickly across the continental U.S. Currently, WNV has a world wide range including most of North America, Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia.

In 2000 the virus was found for the first time in Massachusetts. From 2000-2019 there have been 193 identified human cases of West Nile state wide. Six of the human cases were in the district. There have been horses and other livestock have also been infected with WNV in Plymouth County. The number of infected horses has decreased significantly since the introduction of a vaccine for horses.

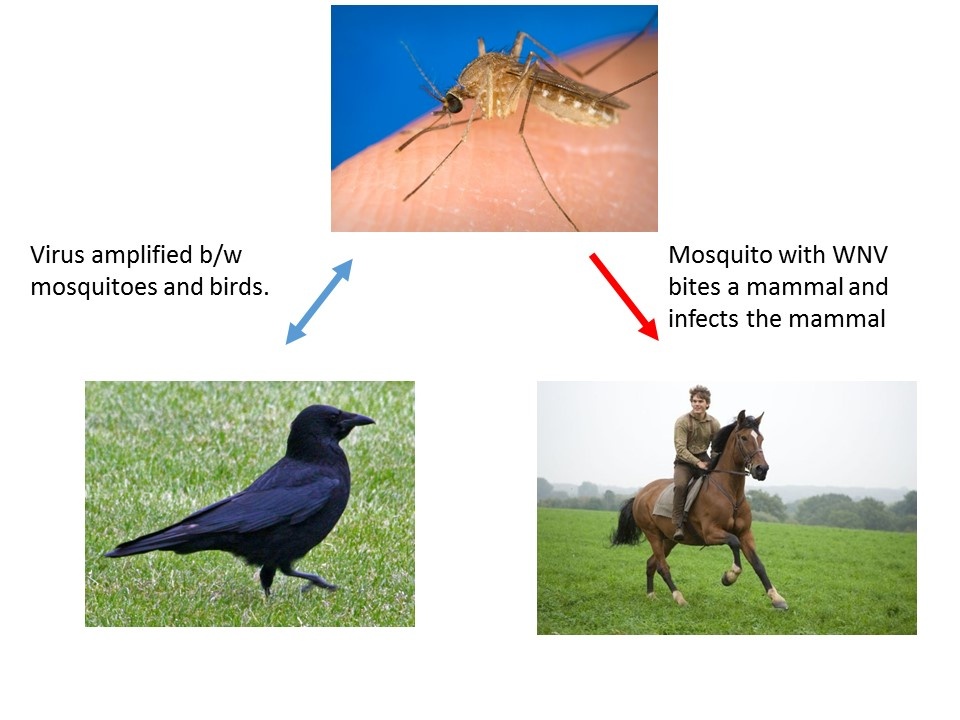

Transmission Cycle

- In the summer, WNV is maintained in a bird-mosquito cycle. Where mosquitoes infect birds which in turn infect more mosquitoes. Over the summer, the number of infected mosquitoes increases.

- Animal infections are not part of the virus maintenance cycle. Human cases usually occur later in the summer when the virus is more common in the mosquito population.

- The mosquito responsible for most human infections is the common house mosquito (Culex pipiens). The immature mosquito is found in containers and polluted water. As a result the common house mosquito is closely associated with people.

How do I prevent mosquitoes?

- Remove water holding containers such as buckets and tarps from your property.

- Dump and drain items such as toys and unused kiddie pools

- Keep gutters clean.

- Rinse bird baths once a week.

How can I prevent mosquito bites?

- Use EPA registered insect repellents.

- When possible wear long sleeve shirts and pants.

- Avoid being outside at dusk and dawn or when mosquitoes are active.

What is PCMCP doing?

- Conducts public education.

- Submits mosquitoes to Massachusetts Dept. of Public Health for testing.

- Applies pesticide to catch basins in the district.

- Treats stagnant water.

- Collect tires.

- Increase adult mosquito control in areas with virus activity.

Finally, the public has an important role to play in the control of WNV and we work to educate the public about the issue. We visit schools and others to discuss WNV. If you are interested in having us come visit your organization or home, please give us a call at (781)585-5450.

Photo Credits: Culex mosquito By James Gathany, CDC

Other State Action

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MA DPH) manages a statewide network of mosquitoes traps.

- MA DPH tests mosquitoes for WNV virus.

- Public outreach and notifications.

- Arbovirus Surveillance and Response Plan is updated annually.

Overview

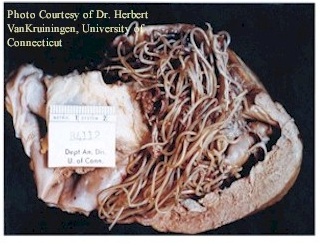

Dog heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) is a parasitic worm that can be life threatening for dogs and other canines. Mosquitoes play an essential part in the lifecycle of the worm. Dogs and sometimes other animals such as cats, ferrets and raccoons are infected with the worm through the bite of a mosquito carrying the larvae of the worm. While cats are susceptible to the disease they do not appear to be good hosts. Dirofilaria immitis is found throughout much of the United States including Massachusetts. Many mosquito species in Massachusetts can become infected with the worm.

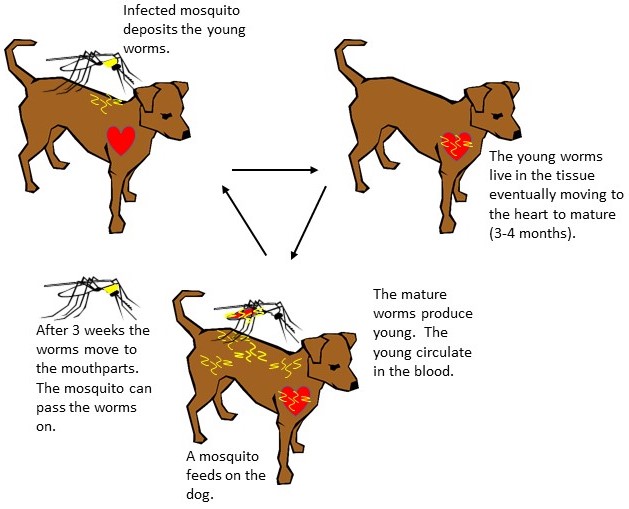

Lifecycle

Dirofilaria immitis is dependent on both the canine and the mosquito to fulfill its lifecycle. In an infected dog the adult worms are 9-16 inches in length and live in the dog's heart and lungs. The young worms circulate in the blood stream of the dog. These worms must infect a mosquito in order to complete their lifecycle. Mosquitoes become infected when they blood feed on a sick dog. Once inside the mosquito they live in the body of the insect, where they develop for 2-3 weeks. When they are in their 3rd stage of development they move to the mosquito's mouthparts, where they will be able to infect an animal. When the mosquito blood feeds, the young parasites are deposited on the surface of the skin. They enter the skin through the wound caused by the mosquito bite. The worms burrow into the skin where they remain for 3-4 months. If the worms have infected an unsuitable host such as a human the worms usually die at this point. If the larvae are in a suitable host they will enter the blood stream and locate the heart of the animal. Once they are in the heart they will reach the adult stage after about 5 months. In all the lifecycle of Dirofilaria immitis takes about 9 months to complete.

Symptoms and Detection

Symptoms are not usually apparent until the adult parasite have damaged the heart and other organs as a result of reduced blood flow. Some of the symptoms include:

- Weight loss

- Shortness of breath

- Chronic cough

- Chronic heart failure

- Death

Prevention is the Best Treatment

The best way to deal with dog heartworm is to prevent your dog from becoming infected. Your veterinarian can prescribe medications to prevent your do from getting infected.

Treatment

Curing dog heartworm can be an expensive and risky. The goal of treatment is to remove the adult heartworms, prevent reinfection and minimize complications. If our dog has heartworm your veterinarian should evaluate your pet and decide the best course of action.